The Wolsey Gospel-Lectionary and Its Provenance

Published on 11/05/2017 | Originally published 2005, draft for a CD-ROM

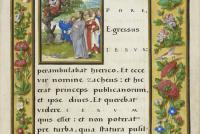

There is no doubt that both Magdalen College’s gospel-lectionary (Magdalen MS. Lat. 223) and Christ Church’s epistle-lectionary (Christ Church MS. 101) were commissioned by Thomas Wolsey, for his initials and coats of arms make frequent appearances in the borders. It is possible that Wolsey intended the lectionaries for his new college foundation in Oxford, since the feast days celebrated in both volumes match those mandated in Cardinal’s College statues of 1526. This is suggestive, but does not entirely rule out the possibility that the lectionaries were made for Wolsey’s own use at one of his private chapels.

It is certain that Wolsey chose one of the best available scribes, Pieter Meghen (1466-1540), to write his book. Meghen’s other patrons included Henry VIII, the German astronomer and humanist Nicolaus Kratzer (1487-after 1550), the English humanists John Colet (c. 1467-1519) and Christopher Urswick (1448-1522). He knew Thomas More (1478-1535) and Erasmus (c.1469-1536), who, in his correspondence Erasmus called Meghen ‘Cyclops’, ‘Unoculus’, and ‘Petrus Monoculus’, for his one-eyed vision. He worked with the most skilful illuminators too, including Hans Holbein (1497/8-1543) and the Horenbout family, but it is not clear who did the artwork in the two Wolsey lectionaries: Elizabeth Morrison named Meghen’s unknown collaborator The Master of Cardinal Wolsey (see her essay in the Technical Analysis section of the CDROM). Although Meghen usually signed his earlier work, the Wolsey lectionaries are unsigned, possibly because Meghen’s distinctive ‘continental humanist bookhand’ would have been readily recognized by then. It might seem remarkable that Wolsey commissioned manuscript books, when printed books had been available in England since Caxton had set up his shop in Westminster in the mid-1470s, and on the continent for decades before that, but the handwritten-book tradition continued strong in the sixteenth century, and would have been uniquely appropriate for such a prestigious job. Indeed Pieter Meghen sometimes used printed books as models for his handwritten work.

The lectionaries have been dated to about 1528-9. Again the evidence is internal: the Christ Church manuscript is actually dated 1528 in the vertical borders of folio 32. Whilst the Magdalen gospel-lectionary was probably illuminated the following year, after Wolsey was sure of becoming bishop of Winchester, for the Winchester arms appear in this volume only. The text itself was probably written by Meghen earlier, for it does not include the requisite Winchester saint’s day of St Swithun.

If Wolsey had intended the lectionaries for his new Cardinal’s College (now Christ Church), they did not immediately make it there. Indeed it is possible that Wolsey never saw the finished volumes. Henry VIII had been adding sequestered monastic books to his library from the late 1520s, when he was investigating the possibility of divorce from Catherine. Many bear the initials ‘TC’ – probably for Thomas Cardinal, that is Cardinal Wolsey, who assisted in this project; and most were stored in Henry’s libraries at Westminster, Hampton Court, and Greenwich. After Wolsey’s downfall in 1529 and death in 1530, Henry confiscated his books too, including these gospel- and epistle-lectionaries. It is tempting to believe that the pair may have been described in a post-mortem inventory of Henry’s goods.

Received at Greenwich on the ninth of July from the ‘kinges Juelhous in the chardg of Sur Anthony Auchar knight, master and treasurer of the same’ were four ‘books [i.e. two pair] of Gospelles and Pistelles covered with silver and guilte’. One pair is promising:

“Item a Gospell booke thone side plated with silver and evill gilte havinge at corners on plates Marke, Mathewe, Peter, and Paule on thone side, lackinge claspes and one round pece of silver, wenig [sic] with the bordes, leaves, silver, and fyve bullions of latten on thother side poizcxxx oz.

Item a Pistell booke like the booke afore, plated with silver and evill guilte and Luke John, Peter, and Paule on thone side, lackinge claspes and a rounde pece of silver, weinge with the borders, leaves, silver, and fyve bullions of latten on thother syde poiz cxxi oz.”

The gospel-lectionary described here weighed more than eight pounds in that lavish binding, while the Magdalen manuscript weighs about five pounds in its present calf-over-pasteboard binding; the epistle-lectionary in the inventory weighed more than seven and a half pounds. Wolsey’s well-known penchant for the luxurious lends support to the thesis that his two volumes were bound in this way (see Steven Gunn’s ‘Wolsey’s Patronage of the Arts’). Nevertheless, as Mirjam Foot shows in her close analysis of the binding (‘The Binding of the Wolsey Gospel-Lectionary’), there is no practical evidence to support a theory that the Magdalen and Christ Church manuscripts appeared first in treasure bindings that were later replaced, and it is unlikely they are the pair described in the Henrican inventory. For one thing, Magdalen’s pasteboard binding could not have supported a heavy silver-gilt binding.

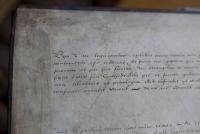

In 1556 the gospel-lectionary was almost certainly in Winchester, and, again, the evidence for that is in the volume itself. The text of an oath taken by Thomas White, who was standing in for his brother the new bishop of Winchester, John White, is written on its first pastedown (the blank leaf of paper that is literally pasted to the front board of the binding). White’s appointment was somewhat contentious, in that Reginald Pole had hoped for the post, and then agreed to give up any claims in return for an annual payment from Bishop White of £1,000. John White was nominated 16 May 1556; the date of provision by the Pope was 6 July. The proxy oath suggests that the lectionary may well have found a temporary home in the bishop of Winchester’s library in the mid-sixteenth century.

The connections between Magdalen College and Winchester go back to the College’s foundations in 1458 by William Waynflete of course, who was himself bishop of Winchester, succeeding Henry Beaufort in 1447. The bishops of Winchester have been official College Visitors ever since, and many of their visitations are recorded in the College Archives. During the mid- to late sixteenth century it seems to have been a tough job, requiring intervention in numerous college disputes and a familiarity with the people and issues involved. Entertainments and exchanging of gifts often played a part in such occasions, and it is just possible that one of the College Visitors presented the lectionary to the College during one of his visits.

It is more likely that the volumes left the bishop of Winchester’s library by other means. John White was the last Roman Catholic bishop of Winchester, under the reign of Queen Mary. He was deprived of his bishopric in 1559, died the following year, and was replaced by the Protestant Robert Horne. It is possible that Winchester books deemed too overtly Roman were dispersed or destroyed then, and that may have been when Samuel Chappington – whose signature is on the first fly-leaf of the Magdalen manuscript – or another member of his family acquired the book.

If the Winchester library was purged of this volume after 1560, that may have been when it was rescued by one of the Chappingtons. Certainly there are stories, some of them involving far-sighted members of Magdalen College, of other manuscript books being rescued from the Reformation during this period. We know little about Samuel Chappington, but fortunately he has an unusual surname, which suggests his almost certain association with the Chappingtons of South Molton, Devon. They were a family of organ-builders, and it was no doubt one of Samuel’s relations who built the organ for Magdalen College Chapel in 1597: the College’s account books for that year record that John Chappington was paid £33.13s.8d for constructing the organ. He was paid another two pounds for repairs to the organ the following year.

The only Chappington will recorded in the early Chancery probate records is that of the same John Chappington, who is the most famous member of his family; a search of the Devon Country Record Office revealed no others. Unfortunately there is no evidence to construct a story of the dying John Chappington describing the wonderful lectionary his relation Samuel had given him and that he intended to bequeath to Magdalen College. Indeed his will mentions no books at all. It is in other respects a rewarding, and sometimes surprising document.

Coincidentally the circumstances around the gift of the epistle-lectionary to Christ Church shed some light on John Chappington’s will: Christ Church College recorded receipt of the lectionary in 1614, and that it was given by John Lante. Lante had been associated with Christ Church since about 1564, when he was a chorister there; he became a student in 1572, took his BA in 1576, and his MA in 1579. In 1594 he was licensed to practise medicine. He may have been influenced to donate by the fact that Wolsey had founded Christ Church and had perhaps intended the lectionaries for his new foundation.

John Chappington, organmaker of Winchester, drafted his will on the 26th of June 1606. Although clearly very ill and ‘lyke to dye’ according to his executor, Chappington wrote that he was of ‘good and perfecte memorye’. In that state, his first concerns were to commend his soul to God, provide for his burial in the Cathedral Church at Wells, and to pay 20s. to the ‘singingmen and Quiere there of the same Church’. He gave other small sums to various relatives, but the most significant gift is to his godson John Colsen of ‘a pair of virginals in the possession of my Lord Bushopp of Winchester’. The will establishes that Chappington was a lover of music, normally lived in Winchester, probably died in or near Wells, and had an association with the bishop of Winchester. Most of the rest of the probate copy is taken up with a reconstructed discussion between the dying man and William Budd, his executor, where Budd implores John to involve his brother Ralph Chappington in the executorship. Evidently Chappington insisted over and over again that his brother was ‘verye troublesome’ and only William Budd could do the job. The will ends: ‘William Budd replyed and said is yt not your pleasure that your brother Ralfe shalbe ionyed with me and hee answered noe.’ Two witnesses sign the will: William Colson and John Lante, the same John Lante who gave Christ Church its lectionary.

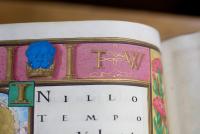

So a fairly clear line of provenance for the lectionaries can be drawn from Cardinal Wolsey’s original commission in the late 1520s to Henry’s confiscation of them after Wolsey’s downfall. The Magdalen manuscript was in Winchester by 1556, and then in the possession of the Chappington family. It seems likely that one of the Chappingtons presented the volume to Magdalen College at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Possibly John Lante, who gave Christ Church its Wolsey lectionary and witnessed John Chappington’s will, was involved. Certainly the gospel-lectionary was in the Magdalen College library by the early eighteenth century, when Thomas Hearne the antiquary described ‘a very curious MS. call'd Cardinal Wolsey’s Missal. It is admirably well illuminated. T.W. is frequently in the Book.’